While using the rather decrepit (but at least in the same dorm building) computers in Scotland, I managed to make an appointment for the following week via email with the University of Sussex Special Collections -- before my eyes gave out on the technicolor acid trip screens. Dalkeith, Scotland: beautiful in nature, not so much in technological comforts.

Anyway, the Special Collections librarians at Sussex work remarkably fast. After requesting a date and time, and specifying what works I was interested in viewing I am set (in the Bloomsbury Archives, the Monks House Papers were first made available to Quentin Bell, Virginia Woolf's nephew, to write her biography. Which, I should say, was totally against her wishes. As much as Ms. Woolf was fanatical about writing, as well as in general, she specifically stated in her suicide note, that her husband Leonard should destroy her papers once she, well, drowned. In some respect, I do appreciate Leonard's denial, since I reap in the benefits. But it's sad that Virginia, who fought to regain power as a woman, and certainly in her literary life, was in the end denied her final request. But I digress!).

The Monks House Papers falls into three groups: letters, manuscripts, and press cuttings. As I was intending to visit the British Library at least once more (they have a good collection of secondary material on Woolf, as well as all of her journals), needing to put my shiny reader's card to some use -- other than adding to my already well-established collection of horrible ID photos -- I decided it best to narrow my selection to biographical manuscripts. It turned out to be a wise decision indeed because Virginia? She must've been on very close terms with the postal service. The woman, if anything, was prolific.

Armed with some knowledge of Virginia's upbringing, I was interested in how Virginia saw the events as they unfolded, and in retrospect. But first, I had to get my foot in the door.

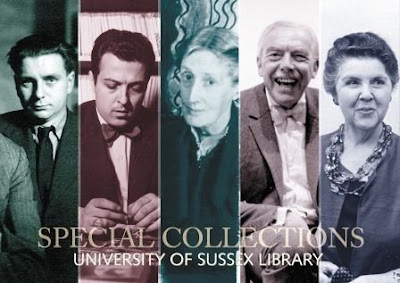

Like most places in the UK, security is enforced, no ifs, ands or buts. The student worker at the door was nice enough, though, once I explained that I had an appointment and did indeed have proper identification. To even enter the university library you need a current student ID card; but thankfully I was granted a day pass, seeing as I was prepared for once. Scanning my bar code, pushing through the turnstile, I make my way upstairs to the Special Collections.

It's a small space, and the librarian at the desk kindly shows me where the lockers are to store my things -- other than a notebook and pencil. She retrieves the boxes I requested, and it's rather wimpy of me, I suppose, but I take one at a time. Loose manuscripts, they're hefty literary loads.

And then it's all Woolf. I won't get into painful detail, other than thank goodness for typed transcriptions. Everything I had access to wasn't the original source (they're photocopies), so that took some worry off my head; it's easier to concentrate on the material's content without having to stress myself over ruining the items themselves. Hopefully, it will come to some good in my research paper. Whatever else, it was like watching a Victorian telenovela unfold. Dead half-sister's husband arriving to propose to other sister, while everyone is still black in mourning? Check. Commenting about nephew-who-was-killed-in-the-war's sexual exploits? Check. Father substituting step-daughter in lieu of dead wife? Check. It's disturbing to the extreme, the shades of incest, gender inequality, and death that pervades Woolf's life and works. It's partly why so many biographers choose to cast her as fragile, her mind torn away by what went on behind closed doors.

Still, Woolf isn't one thing, one quality -- no one is. For all the ambivalence in A Room of One's Own, there's a note of persistence. For all the fire in Three Guineas, there's wariness of that anger. She's been criticized for racist comments, egotism, intellectualism, indifference to class. Margaret Thatcher doesn't like her at all. But Woolf is one of the core figures in feminist discussion today, in literary circles. Her works speak to us still, and for all her faults, she is with us for a reason.

Woolf may have drowned herself in a river in Sussex, near where the university that houses her papers stands, but her heart speaks of her struggles in London; as a woman wanting change; as a political activist. Woolf is as large as she is small, personal as she is private. She has something to say, and how we hear it is open to interpretation -- reinterpreting the text as much as the source.

Resources:

University of Sussex Library Special Collections homepage

Monks House Papers

Images courtesy of the University of Sussex Library